Between November 21 and November 24, 2025, one of the most dangerous software supply chain attacks in recent history unfolded inside the JavaScript ecosystem. What made it uniquely alarming was not just the number of infected packages — but the speed, stealth, and self-propagating “worm” behavior of the malware.

For thousands of developers, a routine npm install silently became a credential-stealing operation that exposed:

These secrets were then uploaded to public GitHub repositories, where attackers and automated scrapers could freely harvest them.

This article explains what happened, how the malware worked, who is at risk, what it means for SEO and websites, and what actions organizations must take immediately.

If you’re a developer, running npm install is as routine as checking email. You use it every day. You trust it. And normally, that trust is justified.

But during a four-day window in late November, attackers successfully turned that trust into a weapon.

Developers who installed certain popular packages during that period unknowingly executed malicious code automatically during the install process. That code did not display errors, crash projects, or show obvious warnings. Instead, it quietly scanned machines for secrets and uploaded them to attacker-controlled GitHub repositories.

Most people never noticed.

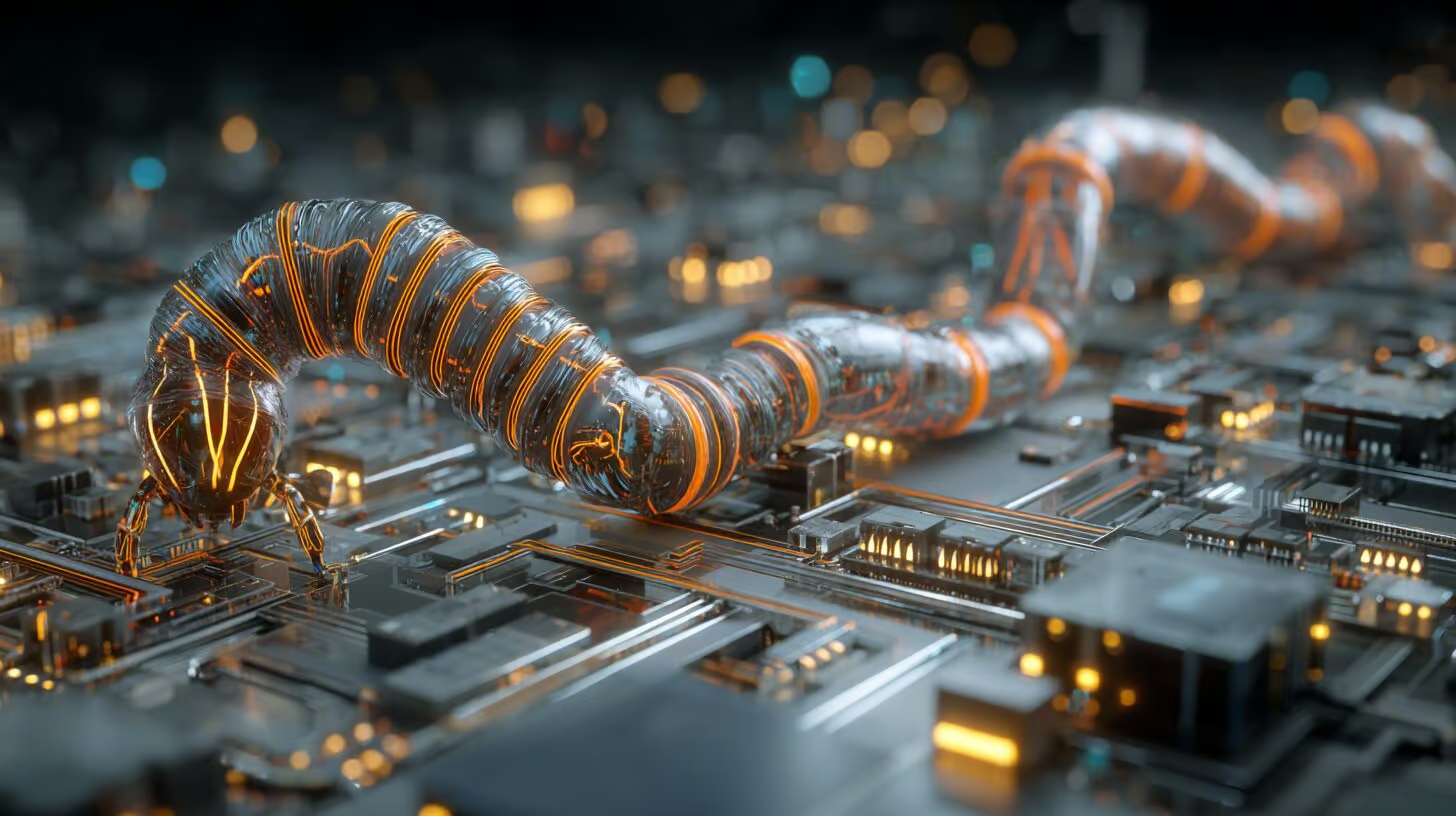

This was not a single compromised package that could be patched and forgotten. It was a self-propagating worm inside the npm ecosystem. Once it infected one developer, it used their stolen credentials to compromise additional npm packages — which then went on to infect more developers.

The attack spread exponentially.

In just a few days:

A supply chain attack doesn’t directly hack end-user organizations. Instead, attackers compromise trusted upstream components — software, libraries, services, or vendors — that many organizations rely on. When those upstream components are pulled into production systems, the attackers ride along invisibly.

In modern development:

In this case, attackers targeted npm package maintainers, not companies. Once a maintainer account was compromised, publishing a malicious update became trivial — and that update propagated automatically into downstream projects.

Attackers used social engineering and credential phishing to steal:

Once they had maintainer access, they didn’t need to “hack” npm itself. They simply used legitimate publishing mechanisms.

New versions of trusted packages were released — but with malicious install-time payloads embedded inside them.

High-download packages were especially devastating because:

When developers ran:

npm installnpm cinpm updateyarnpnpm install…the malware executed automatically during lifecycle hooks such as:

preinstallinstallpostinstallNo warnings. No prompts. Just silent execution.

Traditional malware compromises a machine and stops there. This attack went much further.

After stealing credentials, the malware:

This created a recursive infection loop.

Security researchers dubbed the malware “Shai-Hulud”, after the massive sandworms from Dune — a fitting metaphor for something that spreads invisibly beneath the surface and multiplies through consumption.

The malicious payload ran inside npm lifecycle scripts. That means it executed:

There was no need for user interaction.

The malware harvested:

.env filesThe scan covered:

.ssh directories.npmrc files.gitconfigStolen secrets were uploaded to:

Using GitHub for exfiltration allowed the attackers to blend into normal development traffic and evade many forms of network-based detection.

Attackers can:

Attackers can:

Attackers can:

Attackers can gain:

| Metric | Impact |

|---|---|

| Infected packages | 425–500 |

| Monthly downloads affected | ~132 million |

| Compromised GitHub repos | 25,000+ |

| GitHub tokens stolen | ~775 |

| AWS credentials stolen | ~373 |

| GCP credentials stolen | ~300 |

| Azure credentials stolen | ~115 |

This was not theoretical. This was an active, large-scale exploitation of production environments worldwide.

You should assume possible exposure if:

.env filesIf you are unsure: assume compromise until proven otherwise.

This incident is not only a developer or IT problem. It has direct SEO, indexing, trust, Discover, and brand-risk implications.

If compromised JavaScript reaches production, it can:

This may lead to:

With CI/CD or GitHub access, attackers can:

noindexEven temporary exposure can knock a domain out of:

When tokens are rotated, teams often forget:

Stolen infrastructure credentials can be used to:

Modern ranking systems treat security incidents as brand-level trust scoring events. Public transparency and remediation directly affect recovery speed.

Can this happen again?

Yes. Supply-chain attacks are one of the fastest-growing threat vectors in software security.

Is this only an npm problem?

No. Every package manager ecosystem (Python, PHP, Ruby, Go, Java) carries the same structural risk.

Does this affect non-developers?

Yes. If you run software built with compromised dependencies, your users and data may be affected.

This npm supply chain attack marks a turning point in modern software, cloud, and search-trust security.

It proves that:

If you act quickly, rotate credentials, audit infrastructure, and harden your supply-chain controls, the worst-case outcomes can still be prevented.

What matters now is not whether the ecosystem was vulnerable —

it’s whether your organization responds decisively enough to stay secure and trusted.